篆刻: Seal Engravings

Note: A lot of this information comes from the YouTube channel 篆刻専門店かまくら篆助の篆刻日和 (Roughly "Tenkoku Specialty Store Kamakura Tensuke: Engraving Weather") run by 雨人 (Ujin). He is a professional and has studied the trade in China where the craft originates and is therefore a firsthand source, but there is the possibility he is incorrect about things.

I take no responsibility for incorrect information provided by this source.

What are Seal Engravings?

Seal engravings, also called 篆刻 (tenkoku) in Japanese, are stamps carved from soft stones that are used in various contexts.

Seal engravings is quite long, so for the rest of this article I will be calling them tenkoku for convenience.

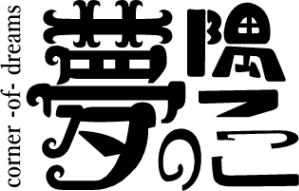

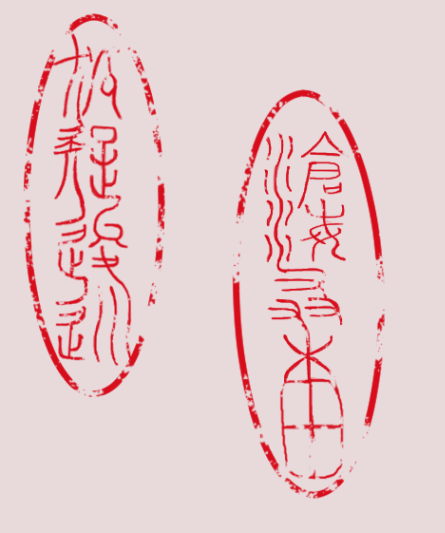

Originating from ancient China, tenkoku were originally used much in the same way wax stamps were on letters- messages in that era were often written on bundles of bamboo and tied together, with the rope secured by a bundle of clay that the sender would then stamp with their signature to inform the recipient that the message came from them. After writing on bamboo fell out of favor and paper took over they fell into disuse, before eventually being dug up, re-discovered, and repurposed by the Chinese. Eventually, the Japanese imported them to their own country for their own uses, which is what I will be covering here. Below are a few examples of tenkoku:

Tenkoku in the Modern Day

In modern day Japan, tenkoku are primarily used as a substitute for a signature: the average person might have a tenkoku commissioned for signing their 年賀状 (nengajo), or New Year's greeting cards, as a form of 判子 (hanko), or stamp, but recently more general stamps that include pictures or generic phrases seem to be more popular- nowadays they are more often seen as a signature for artists and calligraphers. The latter, in particular, have a fairly deep culture and etiquette surrounding tenkoku that I would like to dive into later.

Tenkoku Format and Character Types

The characters in tenkoku are not just standard Japanese kanji, they are written in various different forms and orders to be aesthetically pleasing- they are a signature after all.

白文 (Hakubun) and 朱文 (Shubun)

Tenkoku come in two major varieties: 白文 (hakubun) and 朱文 (shubun). These translate roughly into "white characters" and "red characters" and the difference is, essentially, whether the negative space is the characters themselves or the space around the characters, respectively. Hakubun has the characters themselves dug directly out of the stone so that when stamped their negative impression is what you see. Shubun, on the other hand, digs out the space around the characters, so that when stamped the characters are in ink and the space around them is white.

The reason these two have the names they do, and why tenkoku are only ever red, comes down to the origin of the ink used. Called 印泥 (indei), roughly "seal ink/seal mud", the traditional method of making it seems to be using cinnabar along with lotus fillaments as a binding agent to make thick ink (link), but I don't know what the modern production method is- almost everyone buys it from manufacturers so it's hard to find any information on it. Different manufacturers also put different ingredients into the ink to change its color, with some being brighter or darker, or being cheaper or more expensive (video of Ujin trying different brands).

篆書体: Seal Script

The main character type used is called 篆書体 (tenshotai), or "seal script" (also sometimes called 小篆 (shoutai) when it's smaller). Kanji characters originally evolved from pictograms, and the goal of tenshotai is to bring the characters back to a halfway point between those original pictograms and something legible. This practice has evolved over the thousands of years the craft has been alive, and there are various dictionaries available for purchase that document popular interpretations of kanji through the ages.

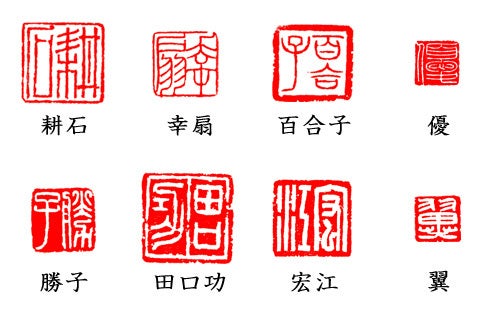

One variant of tenshotai that is quite independent from this, though, is called 九畳篆 (kujouten), or "nine-fold seals", roughly. Kujouten eschew the pictogram aesthetic altogether for something completely different: each kanji is represented by a series of lines that only ever take right angle curves, and in the end those lines must neatly fill up a square area. The result is a long, snakelike series of lines that fill into a complex pattern.

While most tenkoku are square, there are all variety of shapes- rectangles, ovals, and circles are not unheard of.

Ordering

Though the majority of modern Japanese is read left to right horizontally, like English, traditional Japanese is actually completely different: the traditional way of writing is to write vertically, and right to left. The fact that manga are read right to left, for example, is a well-known side effect of this history. Tenkoku follows this format, with the kanji being written in this order. Beyond that, however, there is some flexibility.

One character simply fills the block, obviously, but two characters can be written on top of each other or next to each other, and when you get to three characters you can have them all aligned horizontally, or you can write two on top of each other and stretch the third one vertically to fill the space. Four characters is normally the limit of a traditional square-shaped tenkoku with all four being squished into evenly sized boxes. There seem to be some craftsmen willing to do five characters and beyond, but it is very rare.

Below are some examples of possible formats for a tenkoku:

落款印: Tenkoku in Calligraphy

The following, including images, are lifted from this website: (link)

While tenkoku are used in various places, in Japan the majority of the time they are seen in 書道 (shodou), the Japanese calligraphy world. Within this context tenkoku has a fairly long history and specific practices with regards of the types of tenkoku used, where they are stamped, and what is written on those stamps. In this context they are referred to as 落款/落款印 (rakkan/rakkanin), so I will use that name for this section.

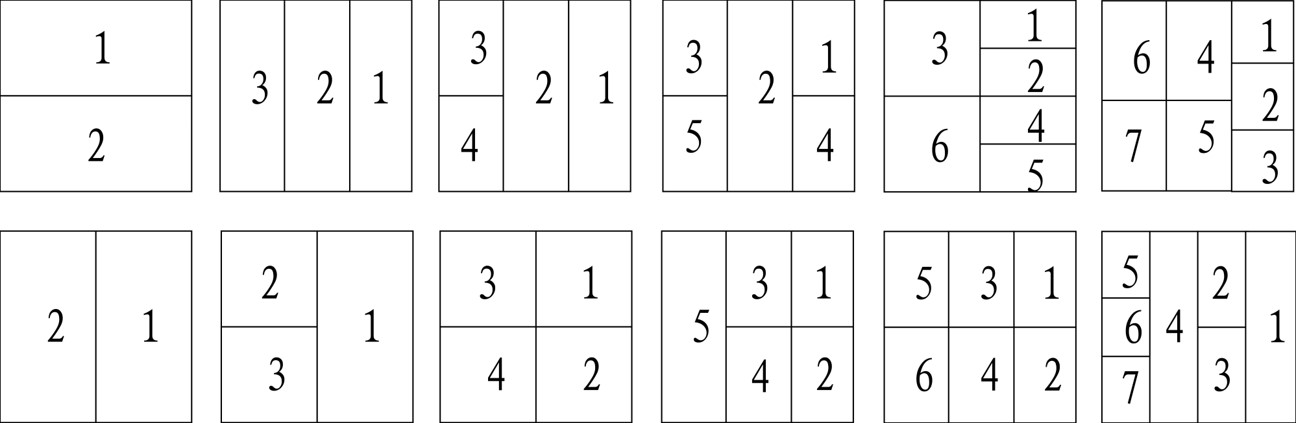

First we will look at this guide:

引首印 (Inshuin)/関防印 (Kanbouin)

The first stamp, in the topright, is called the 引首印 (inshuin) or 関防印 (kanbouin). This stamp is usually a generic catchphrase or saying that the author likes, often a 四字熟語 (yojijukugo/yonjijukugo) (think of them as idioms, basically). Unlike most rakkan, these are often rectangular in shape.

姓名印 (Shimeiin) and 雅号印 (Gagouin)

Next, on the left side from top to bottom are the shimeiin and gagouin. These are both names, but different kinds: the shimeiin is the calligrapher's real name, while the gagouin is something of a pen name, or alias. Typically it is encouraged to use your full name for the shimeiin, but if there are too many kanji in the name (usually more than 5) then it is encouraged to pick your first name. If your first name is spelled with hiragana then typically the person in question picks kanji for their name using 当て字 (ateji), a system where for each syllable you pick a kanji that shares the same pronunciation. The gagouin, on the other hand, can be whatever you want. Apparently it was tradition for apprentices to recieve their gagou from their master once they completed their education, but nowadays it's perfectly okay to simply make your own.

It's unknown where this trend started, but in almost all cases, the shimeiin is hakubun and the gagouin is shubun- it's commonplace to the point that people remark it as being strange if you do something different. The shimeiin is also always stamped on the top, and the gagouin on the bottom.

御城印 (Gojyoin) or 遊印 (Yuuin)

Finally, on the bottom right is the 御城印 (gojyoin), or alternatively the 遊印 (Yuuin). This one is slightly confusing- all the sources I researched say different things about it and in modern times it is rarely if ever included, so it seems like it's on the way out. In the times that it is used, however, it seems to be another free space like the inshuin/kanbouin.

Digital Tenkoku

Given the knowledge we have learned about tenkoku already, we can also have a little fun and create a digital version of a tenkoku stamp for ourselves.

The first thing is to decide on a name. If you're creating a gagouin then the process is easy, simply pick a pen name that you like. There are plenty of websites like this one that have name registries for baby names you can pick from, or you can come up with something original using the previously mentioned ateji system. If you want to make a shimeiin, or use your existing username, it can be a bit trickier, however there are still options. You can either convert your name into Japanese, then use ateji to create your name, or you can translate it directly into Chinese. Depending on how long your name is, though, you might have to shorten it to a nickname.

Once a name is decided on, you have a couple of options: either you can draw it yourself, or you can use online image resources. For drawing, using an online shoutai dictionary, you can look up the characters you wish to draw and use those as reference. Alternatively, using a font is also an option, however it is slightly challenging to find fonts with good coverage. This list has a handful of free fonts, but honestly speaking the coverage on them isn't very good. There are fonts with extremely good coverage, but they're also extremely expensive, at around 10,000JPY or so. If you want to use kujouten, however, you're in luck: there is a Chinese website with a fairly comprehensive coverage of kanji (though obviously it skews towards Chinese kanji over Japanese kanji). Simply search the kanji you're looking for and you'll be able to download a PNG file of it.

Once you find your character references/resources, open up your favorite image program and arrange them how you like! As long as you protect the writing order, you're fairly free to warp, stretch, and alter the kanji as you wish. As a tip: if you want to make a hakubun, you can select the pixels of the characters, invert your selection, fill that selection in on a new layer, and then hide the previous character layer. Finally, at the end it is recommended you add some degredation: a lot of tenkoku craftsmen add artificial weathering to their seals to make them appear older than they actually are. Big pre-ripped jeans energy.

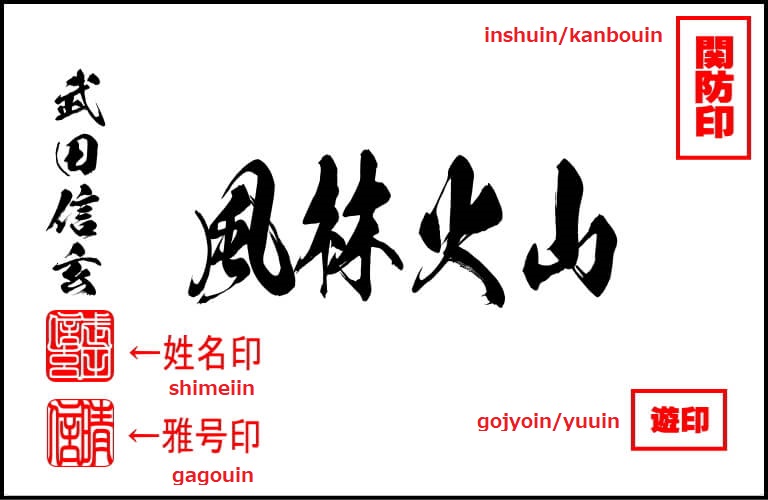

And you're done! Below are a few I made myself, if you want to use them as a reference point:

Conclusion

I always find ancient crafts like this fascinating: despite how old these practices are, they're extremely refined and you can feel the passion and care that goes into each and every stamp a master carves. That goes for a lot of other Asian and particularly Japanese crafts as well: katana metal work, bonsai, even making paint brushes. But I feel like due to the out of the way nature of tenkoku it doesn't recieve a lot of attention outside of Japan and China. I hope this article helps spark at least a little interest in the craft, because I think it's super interesting!